One of my current areas of work is the energy transition in South Africa. In 2022 I co-authored two important pieces on this in the online publication New Frame. Unfortunately, New Frame has since shut down and those articles no longer appear in internet searches so I am republishing them here.

Note that the geopolitics of energy, and gas in particular, changed dramatically in some parts of the world after the Russian invasion of Ukraine, with knock-on effects for the issues described below. We may incorporate those considerations into writing elsewhere.

Gas is a game-changer and the players are plotting

By: Mike Muller

Illustrator: Anastasya Eliseeva

22 Apr 2022

In the second of two articles on the energy transition, the battle for gas exploration in South Africa is explored – and why the production delays in Mozambique suit some interests.

Small but well-funded and vociferous groups of environmental activists and lawyers are blocking exploration for gas both offshore and onshore. They are also now objecting to the construction of gas-fired power stations and facilities to import gas. In neighbouring Mozambique, internal discontent is being exploited by external forces, delaying production at what has been described as a global game-changer for world gas markets.

Yet at last year’s COP26 climate change conference in Scotland, the global consensus was that gas will be a vital transitional fuel. And rich countries, along with their businesses, continue to implement projects that will use gas on their terms and for their profit.

Mozambique’s gas fields, offshore of Cabo Delgado province in the north, are among the most valuable in the region. Over a decade ago, it became apparent that the development of those deposits could transform Mozambique into a major global liquefied natural gas (LNG) exporter. Properly managed, gas development could help transform Mozambique into a middle-income country. But it has also put it on the front line of global energy geopolitics. And this is reflected in the current insurgency and destabilisation in Cabo Delgado.

In January, a consortium led by Italian energy company Eni took delivery of Africa’s first floating gas plant, built in South Korea. Anchored off the coast of Cabo Delgado, it is due to start production later this year. However, the large onshore developments that would increase production eightfold are on hold owing to security concerns.

The consortium led by French company Total, which had already begun to build its production facilities, has declared force majeure and halted work. The United States’ Exxon has delayed its “final investment decision” from 2021 to 2023. Further economic casualties of the conflict include gas-based opportunities for electricity generation and industrial development, including fertiliser production that could have supplied the whole Southern African Development Community (SADC) region.

The security challenges that would be created by Mozambique’s gas reserves were already being discussed in 2010. Not long afterwards, the World Bank warned that the prospect of huge gas revenues might destabilise the whole region, a prediction that has come to pass in dramatic fashion. Corruption at the highest levels of Mozambique’s government left the country effectively insolvent, with former minister of finance Manuel Chang in a South African jail awaiting extradition to the US. The insurgency in Cabo Delgado has required security forces from SADC and beyond to stabilise.

Many roleplayers, many interests

Much attention has, correctly, focused on the domestic drivers of the conflict: inequality, a lack of opportunity and rampant and well-publicised gross corruption by the Mozambican elite. But external forces have also played a critical role. Blackwater, a notorious US security contractor, was seen as a leading contender for contracts to provide security in Cabo Delgado.

Eni is working with China and South Korea’s oil companies, Portugal’s Galp Energia and Mozambique’s national hydrocarbon company ENH, which is a part of all the consortiums. But the full potential of their development will only be achieved when Exxon builds its onshore liquefaction facilities. Total’s consortium includes Asian gas users (Japan, India and Thailand) and is working with Exxon, which has proposed cooperation to reduce production costs for both consortia.

However, Exxon – and the US – have obvious conflicts of interest. Mozambique’s gas development could weaken the dominant position of the LNG market leaders Australia, Qatar and, increasingly, the US itself. Exxon has admitted that the Rovuma Basin discoveries in northern Mozambique and southern Tanzania “will be a game-changer for the world’s energy markets”.

The importance of Mozambique to US energy policy is illustrated by American involvement being led personally by Rex Tillerson, in two separate roles: first as chief executive of Exxon Mobil and then as Donald Trump’s secretary of state. The efforts by Erik Prince, the founder of Blackwater, to gain control of the maritime security opportunities are suggestive. So too is the fact that Mozambique’s loan scandal was driven, in large measure, by attempts to raise money to fund local companies to provide these services.

To put it directly: has the insurgency provided Exxon with a useful excuse to delay the big onshore development that would dramatically expand Mozambique’s production, thereby conveniently protecting Exxon’s other production centres? Even if the Mozambican projects resume, full planned production will have been delayed by some years, keeping world market prices higher to the benefit of existing producers like Exxon. Meanwhile, Reuters reports that the US will be the largest LNG exporter this year.

This perspective on Mozambique and the wider world of global hydrocarbons is relevant to South Africa, and the focus on gas is important.

Skewing the frame

Much of the climate and energy strategies – and legal fees – of South Africa’s non-governmental organisations and civil coalitions appear to be focused on opposing gas-related developments. Their simplistic and populist narrative frames the issues as a choice between apparently cheap and easy renewables or hydrocarbons.

This superficially attractive approach ignores both the costs of replacing the national energy infrastructure and the limits of intermittent sources like wind and solar. And it assumes, without evidence, that a transition from coal-fired power to clean energy can be achieved without using gas.

Drawing on global consensus, the government’s 2019 integrated resource plan (IRP) considered some of the objections that had been formally submitted. It noted that “gas is considered a transition fuel globally and it provides the flexibility necessary to run a system like we have in a cost effective manner. It is cleaner than other fossil fuels. The extent of the gas contained in the draft IRP is within the imposed emissions reduction trajectory.”

Perhaps the problem is that, in energy planning terms, the IRP only provides a short-term perspective, until 2030, that does not reveal the challenge of managing a system with a large proportion of intermittent renewables like wind and solar.

The IRP 2030 scenario projections show that while 33% of the grid’s nameplate generating capacity – the maximum rated output – would come from wind and solar and 43% from coal, those renewables would only produce 24% of the system’s energy compared with coal’s 59%. Nuclear and hydropower would represent just 8.2% of generating capacity, but they produce almost 13% of the system’s energy because they offer consistent and predictable supply at high load factors.

The real challenge will be faced after 2030. As the proportion of intermittent renewables continues to grow, complementary sources of generation or storage must also be increased to compensate for periods in which solar and wind is not available. Complementary infrastructure will likely be more costly and take longer than the rollout of renewables, so delaying it will simply stall the transition.

A place for gas

Faced with this challenge, countries like Germany and Britain, leading advocates for zero carbon strategies, have committed to using gas for another two to three decades as a core element of their energy transition. This is despite their access to complementary sources of power, through Europe’s continent-wide grid to Norwegian hydropower, French nuclear and Danish wind, which will help them manage the intermittency of local wind and solar generation.

South Africa does not have such complementary sources. Critics’ comments recorded in the IRP show little evidence that they had any technically feasible alternatives, let alone suggestions on how to fund them. Proposals were limited to vague “flexible renewable generation” or “energy storage technologies” without suggesting what they would be or how they could be afforded.

One representative from the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research admitted in a radio interview that its proposals simply assumed that storage costs would come down enough over the next decade to make higher shares of renewable energy feasible. Even this is based on the assumption that storage is only needed for a few hours of generation and ignores the risk of the longer-term supply reductions already experienced in Europe and the US. At best, the suggested “all renewable” investment route would put South Africa’s energy security at risk in a way that no other sizeable country is doing.

There is presently no proposed solution that can reliably and affordably provide South Africa’s energy requirements purely from intermittent renewables. While storage technologies are progressing, the cost of long-term (multi-day) storage remains prohibitive. South Africa’s pumped storage schemes are currently among the cheapest technologies for large-scale energy storage, but an installation like Ingula, which can only store enough to generate 1 300MW for less than a day, cost R36 billion.

Costly delays

Important local work on energy storage and the production of “green hydrogen” from renewable energy could be supported since it may offer global opportunities for South African mining and manufacturing. But it will take many years to be brought to scale and deploy, not least because of the massive investment needed in dedicated wind and solar power and Sasol-size production plants.

And, if “green hydrogen” eventually becomes commercially viable, it would best be used to generate electricity in the kinds of natural gas-fired generators that are now being blocked. In this respect, renewable power activism is leading South Africa off course right at the start of the transition marathon.

The latest example is the legal action opposing the construction of gas-fired power stations at Richards Bay and Durban that are to be fuelled by imported gas. But one reason for these developments is that gas exploration onshore and offshore has been repeatedly delayed.

It is the failure to develop local gas resources that has allowed the much-criticised Karpowership “emergency” generation proposal to succeed. The ship will burn gas and it requires no local production or importation infrastructure, offering minimal local development benefits.

South Africans need to stop their dangerously narrow focus on one particular element, or definition, of the energy transition and think much more carefully about how to achieve a genuinely just and viable transition.

The question also has to be asked: who benefits from the current rush to privatised forms of renewable energy, especially since it does not take seriously the interests either of workers and the impoverished in general or economic viability and national sovereignty?

Seán Muller does not receive any funding, or have any other conflicts of interest, related to the subject of this article.

Mike Muller’s pension is invested in, among others, renewable and conventional energy and construction companies.

First published by New Frame.

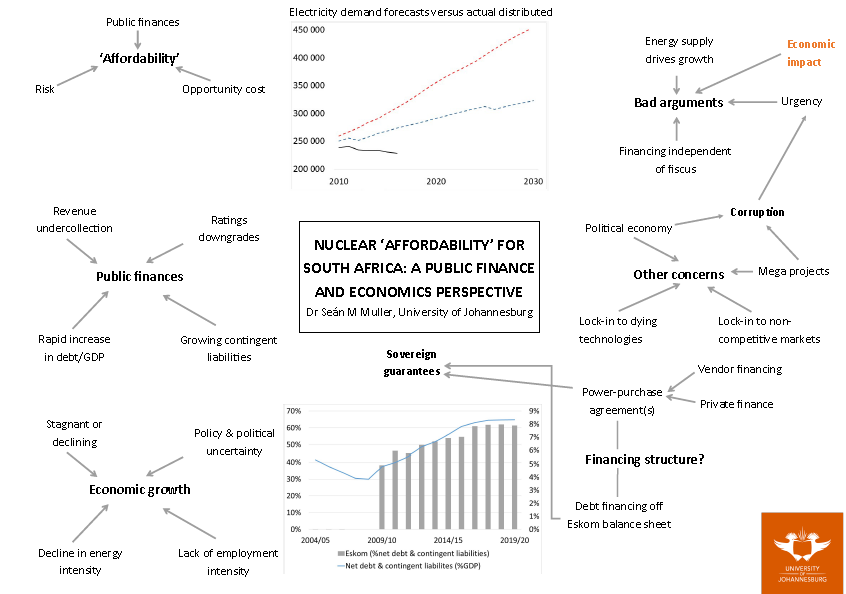

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).