On the 18th of May I attended Nuclear Power Africa, a full day programme on nuclear energy within the broader African Utility Week. I was a little surprised to be invited as a panelist given what I had written previously (here and here) and because I anticipated that an industry conference would be heavily pro-nuclear. As it turned out, I may have been the only panelist who did not have some kind of, direct or indirect, interest in large-scale nuclear procurement proceeding in South Africa. Unsurprisingly, I was also the only panelist arguing that the current case for nuclear is flawed in various respects.

Summary of my argument

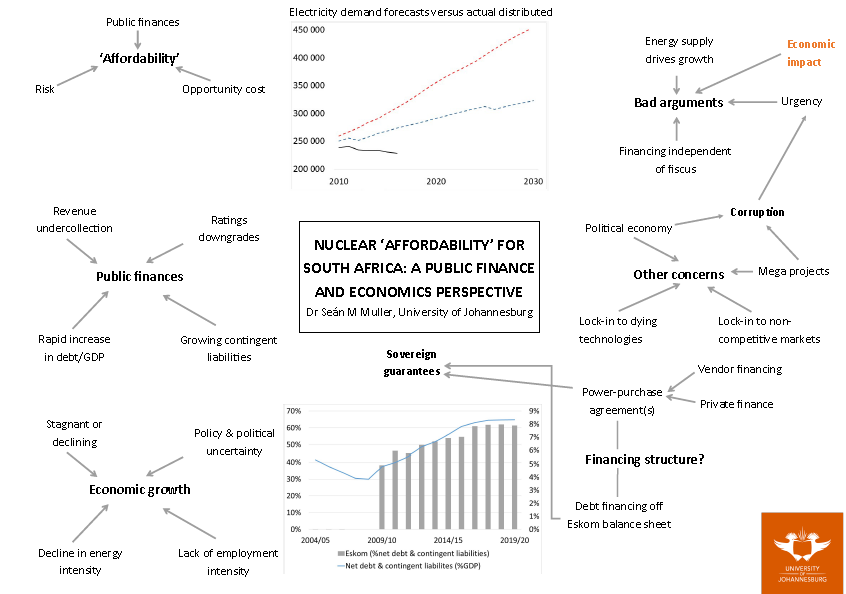

I provided my graphical, one-page summary in a previous post. The basic argument is as captured in my previous articles, but let me briefly repeat it.

South Africa’s public finances are precarious, with stubbornly low economic growth, under-collection of tax revenue alongside additional tax measures, rapid growth in net liabilities (national debt and contingent liabilities such as debt guarantees to Eskom) and of course the recent downgrades – with the possibility of a potentially very damaging downgrade of local currency debt still looming on the horizon.

Meanwhile, electricity demand has not just failed to keep-up with the forecasts from the 2010 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) on which the need for 9.6GW of nuclear was originally based, it has actually fallen. The following graph is striking:

The red dotted line is the original IRP 2010 baseline forecast, the blue dotted line represents a scenario in the IRP 2010 update (from 2013, but controversially never finalised) entitled ‘Adrift in troubled waters’, and the black line represents actual electricity distributed (based on StatsSA data).

There are, furthermore, various ‘qualitative’ concerns about the programme. Among these:

- Nuclear power projects are particularly prone to many of the ills of ‘mega projects, including cost overruns

- This concern is compounded by the fact that in the South African case the urgency behind the project appears to be due to rent-seeking behaviour (corruption) at the highest political levels

- There is a danger of being locked-in to non-competitive markets (e.g. for nuclear fuel) and increasingly outdated technologies.

There is no chance that a nuclear programme will be financed without government guarantees, whether direct, through Eskom or through power-purchase agreements. This means that ultimately government will carry the associated risks. Combine that fact with the above context and I suggest the conclusion is obvious: there is no case for investing in nuclear now. At best, we could revisit the question in 3 – 5 years’ time depending on trends in economic growth and electricity demand.

Notable pro-nuclear arguments and associated debates

Given the above, it was interesting to hear what proponents of nuclear were using to bolster their position.

The arguments for the urgency of nuclear procurement keep evolving, which is a bad sign: it suggests that a decision has already been taken (for other reasons) and attempts are being made to manufacture substantive arguments after the fact. So even while we engage with these arguments, the issue of motive should not be forgotten.

There are two particularly notable issues that came up at Nuclear Power Africa: the argument that policy models which fail to recommend nuclear are flawed; and, the claim that nuclear procurement will be good for the economy and an important part of industrial policy. Despite somewhat more sophistication on some dimensions, I want to suggest that these new arguments are unconvincing, the case for nuclear remains weak and therefore motivations for advocating it appear dubious.

Are planning models for electricity generation capacity wrong?

One of the most damning arguments against the plan to procure 9.6GW of nuclear energy for South Africa is that the models used to plan energy supply no longer recommend nuclear. The notion that 9.6GW of nuclear was needed came from the Department of Energy’s 2010 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). That was based on the assumption of significant growth in energy demand, which has not happened – as shown by the second graph above. Furthermore, the cost of renewable energy in South Africa – as established by recent rounds of competitive bidding – has fallen significantly since then. When these factors are taken into account, the base model used for the IRP and similar models used by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and Energy Research Centre (ERC) do not recommend nuclear. It has been argued (by Anton Eberhard who participated in the Eskom ‘War Room’) that artificial constraints had to be placed on the model used for the draft 2016 IRP in order to produce an outcome in which nuclear is recommended.

The response to this at Nuclear Power Africa, from engineers and economists aligned to institutions pushing for nuclear, was to rubbish the models. This is evidently problematic. If you think a model of this kind has important flaws, then the correct approach is to have a debate about the model structure and parameters. Running the model then rubbishing it because the outcome doesn’t suit your pre-existing conclusion is misguided or disingenuous.

Relatedly, it is concerning that there continues to be a remarkable level of disagreement on even fairly basic technical claims. In a separate session on renewable energy, Tobias Bischoff-Niemz of the CSIR argued that their model accounts for issues like the variable availability of renewables; in the nuclear power session, Eskom’s Chief Nuclear Engineer argued the opposite. And while pro-nuclear speakers cited the example of Germany’s expensive electricity as an illustration of what would happen if South Africa increased its reliance on renewables, Bischoff-Niemz had argued that this was due to Germany investing heavily in renewables at a time when they were much more expensive. It should not be hard to objectively assess these claims.

Economic growth, economic impact and industrial policy

On the economic front, two economists who were in favour of nuclear argued that energy investment must be based on the energy demand associated with the desired level of economic growth. By contrast, I argue that building energy capacity on the basis of wishful thinking could have severe negative consequences for public finances. Rates of growth in economic activity and energy demand are far below what was used to inform the 2010 IRP. It is very unlikely that economic growth will reach the 6% annual growth aimed for in the National Development Plan (NDP) any time soon, if at all. Even the 4% Eskom assumed in its last major tariff application seems improbably optimistic. At best, if economic growth is supposed to be the basis for nuclear procurement, then we should wait a few years in order to get a better sense of the trajectory of growth and how new technologies are affecting the link between growth and the need for electricity from the national grid.

A second set of arguments was put forward by an economist for the Coega Industrial Development Zone, near to where the first nuclear plant might be located. She argued that nuclear procurement would have a significant positive impact on the economy and that even if there was over-investment in energy generation capacity this would be good for industrial development because of low electricity prices.

The economic impact argument is entirely unconvincing. If government indirectly borrows a trillion Rand, either from current or future generations, to invest in anything now that will have an initially large, positive impact on the economy. To paraphrase the famous economist John Maynard Keynes: even if the government just buried that money in the ground and let people dig it up, that would have a large positive impact. The more important question, then, is whether the expenditure is worthwhile: will it provide better social and economic value than alternative investments, and will the debt that future generations have to pay be worth it? At present the answer to both these questions for nuclear is ‘no’. And that also means that this proposal would be bad for the stability and sustainability of public finances.

The argument relating to industrial development is similarly problematic. The positive view that once existed of the extremely low electricity prices South Africa had in the 1990s has been revised. Those low prices were the result of poor management of infrastructure investment: overinvestment in earlier periods followed by a failure of tariffs to include the costs of future investment requirements. But worse still, there is little evidence that the resultant low cost of electricity had any sustainably positive effect on industrial development. The energy-intensive industries that benefitted most are not the most employment-intensive, and have become less so since then. Diverting scarce resources to such industries through an inefficient energy subsidy is a poor argument for nuclear and a bad strategy for Eskom as a state-owned enterprise.

Overall, then, while the arguments for nuclear may be becoming marginally more diverse and sophisticated, but they remain profoundly unconvincing.

The issue of energy generation and industrial policy is, however, a very interesting one on its own regardless of the nuclear debate. Somewhat serendipitously, the Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) Annual Forum happening this week, on the 13th and 14th of June, is on the related topic of “Industrialisation and sustainable growth“.

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).