The debate around the new Finance Minister Malusi Gigaba’s new adviser, Chris Malikane, has gone beyond the deeply flawed proposals he has made, to claims about his academic credentials and integrity. I want to agree that the proposals are flawed, but that some of the attacks on Malikane are as well. Furthermore, they draw attention to some serious issues in South African academic economics that require mature discussion.

Most of the 8-page ‘manifesto’ published, and extensively publicised in various articles and interviews by Malikane, is not worthy of serious analysis. (Although one effort to take it seriously, by Charles Simkins, is worth reading – as is the more acerbic piece by Richard Poplak). It is primarily a political document and contains no substantive content relating to economic policy and public finance. There’s a crude Marxist analysis of class, and a shopping list of things that should be nationalised and services that should be provided. The only interesting assertion is that the working class should throw their weight behind those black South Africans who have become an elite through corrupt government tenders, rather than through credit-based black empowerment schemes. Like the other assertions, no serious justification is provided. But it certainly explains why Malikane’s radicalism has found favour with Gigaba, whose predecessor appeared to be successfully blocking a range of efforts at tender-related corruption by individuals associated either with the President or the Gupta family. The thinking from Gigaba – a man better known by some for tabloid stories, tailored suits, expensive ties and appearances on Top Billing – may have been that Malikane would provide some solidity to the fig leaf of ‘radical economic transformation’, while Malikane – who has otherwise been quietly exerting influence in left-wing, or trade union movements for some time – clearly thought that his revolutionary moment had arrived.

Some have attempted to defend Malikane on the basis of his academic credentials – to the point of also insisting that his evidently wrong-headed proposals (such as ‘expropriating banks’) cannot be criticised except through detailed academic analysis. At which point it is useful to invoke a phrase attributed to the Italian computer programmer Alberto Brandolini: “The amount of energy needed to refute bullshit is an order of magnitude bigger than to produce it”. Just because the minister’s adviser has published some academic papers on other subjects does not mean we must presume that his manifesto carries additional weight. Indeed, the primary disappointment for many who had reasonably high opinion of Malikane up to this point is quite how threadbare his analysis and proposals are.

Where things are getting messy, however, is in attacks on Malikane’s academic credentials. These in fact open-up a big can of worms regarding the state of South African academic economics. (One reason I have been delayed in writing a comment on the Malikane’s saga is that I had been drafting a conference paper on what ‘decolonisation of the curriculum’ might mean for South African economics).

Understanding Peer Review in Economics

It turns out that the issue of decolonising economics is closely related to some of the misguided aspects of attacks on Malikane. The first, by Stuart Theobald, starts off well enough by noting that Malikane’s published, peer-reviewed work either has relatively little relation to his recent arguments or even – in some cases – seems to contradict those arguments. This is a particularly useful point to make for those who, naively, argue that Malikane’s arguments must be substantive because he has published some academic papers. Where Theobald strays into dangerous territory is in his inferences about Malikane’s integrity and assertions about the wonders of academic peer review.

Theobald’s characterisation of peer review in economics makes me suspect that he has never published anything in the discipline. Very few academics I have come across or read, including Nobel prize winners, have such a rosy view of the peer review process; in practice it is far from the notional ideal of a meritocratic system in which originality and quality are what determine publication. And any problems – of cronyism, bias toward researchers in certain institutions, ideological influences and so forth – are amplified if the basic thrust of your work is critical of, or very different to, the dominant narrative. It does not surprise me that Theobald, given his demographic, views on economic policy and his area of work (banking and finance), might not be able to appreciate this.

Which brings us to the issue of whether Malikane is dishonest for publishing work with conclusions he does not agree with. My short answer: no. It might be inadvisable, and it is something I personally try to avoid doing (at some cost), but the system is structured in such a way that it can self-sabotaging to only publish what you believe rather than what you can do. (Some have suggested that there should be betting markets in which economists show their confidence in their empirical claims by putting money on it). Either you will publish in journals not recognised by your peers, or your career will stall at a junior level – and the associated administration and teaching burdens limiting the very time you need for that ‘against the current’ research that is so good it breaks into the mainstream. When co-authors are involved this is even more difficult. These challenges are essentially what Malikane is gesturing at when he says, quoted by Theobald:

Don’t confuse my academic writing and what I believe to be true…you know the business of publishing is so ideologically poisoned that what is published is not necessarily scientific…we sometimes write in order to simply play in the publishing game…not necessarily because we think what we publish is correct…there is heavy ideological repression in academia…

Theobald paints this as sinister and possibly an “act of intellectual dishonesty”. He softens that with a few acknowledgements that Malikane is basically right, but then returns to a naive notion of academic publishing.

Finally, Theobald makes the important point that we should not try and judge Malikane the person but rather “whether he has good evidence and reasoning for his claims”. Unfortunately, he then goes completely off the rails by saying that: “until [Malikane] publishes them in a way that involves assessment by his peers, we must assume he does not”. Which peers? In what journal? I doubt Malikane would have trouble publishing in the Review of African Political Economy, but would Theobald accept that as adequate? (Leaving aside that he is not an academic economist, so it’s not clear what basis he would use).

Regardless, as an academic economist who has also worked in the public sector, I would never accept a policy claim just because someone had managed to publish a paper on it; the idea that successful peer review in economics shows that a claim is ’right’ is completely misguided, and any economist who advised a minister on that basis should also be fired.

There Are Many Flavours of ‘Bogus Economist’

This usefully brings us to the even more problematic contribution by Co-Pierre Georg. Let me start by saying that I was interested, albeit surprised to see – in Georg’s somewhat crudely-stated concern about ‘white male patriarchs’ – channelling critiques I myself have made in the past of untransformed gerontocracies and academics behaving like rent seekers. I have, also, for some time been politely raising concerns with various role players about such dynamics at an organisation where Georg has been an associate for some time; I hope Georg is as vocal on such matters of principle within his institutions, and even when it is personally inconvenient.

The basic assertion of Georg’s article is that people should not trust ‘bogus economists’. Hard to disagree with, but the devil is in the detail. In my draft conference paper on decolonisation, I made some similar critiques of the quality of the local academic economics to those discussed by Georg. Beyond that, though, we are again in swampy terrain. Georg’s assertion basically translates as: ‘people should not trust economists I think are bogus, which obviously doesn’t include me, my co-authors, patrons, friends, etc’. It’s not a new trick, including for fake radicals in economics. In a recent comment an otherwise respected senior scholar in macroeconomics (Paul Romer) published a rather disgraceful attack on various other economists for what he calls ‘mathiness’. Among these was one of the most famous female economists of the 20th century, Joan Robinson, who by virtue of her gender, left-wing views, and being dead, was perhaps an obvious target for Romer. Critiques of excessive or inappropriate use of mathematics in economics are as old as the modern version of the discipline itself. But a close reading of Romer’s critique reveals a petty, self-serving definition of the crime: when economists he doesn’t like use mathematics they are guilty of mathiness, whereas when economists he does like (obviously including himself) use mathematics then it’s done properly. Georg’s argument boils down to a similarly crude skeleton. (Romer, incidentally, was then appointed chief economist at the World Bank – illustrating how dysfunctional economics can be in other places).

Furthermore, Georg peddles a version of how economics can inform policy that is popular with certain types of academic economists, but bears little relation to reality. In this model, people who can write the most complex mathematical equations, estimate the most complex econometric models and get published in high-ranked journals are best-positioned to advise on policy. This might be funny if it were not so misguided and, in its own way, dangerous. There are some individuals who have managed to make the transition from producing cutting-edge academic work (by mainstream standards) to giving good policy advice, but it is the exception rather than the norm. The last thing a finance minister needs is some social incompetent who thinks he can figure-out a policy solution by writing down an equation, running a model or looking for a ‘peer-reviewed solution’. If you need an academic perspective, your adviser talks to a deputy director general who gets someone in the research cluster to do it, or outsources it to an academic like Georg.

Yet Georg goes even further, offering to define for us what a ‘proper academic’ is. But the best he can do in this regard, like Theobald, is to refer to ‘peer review’. I have already made clear that this is a naïve, and in Georg’s case arguably self-serving, use of the notion of peer review. One can tell that Georg, like Theobald, is not exactly familiar with the challenges of swimming against the current. Or, in fact, advising on broad economic policy in the complex South African terrain.

A Necessary Debate

In some ways, the great tragedy of the Malikane saga is that, in principle, he should have been in a position to be a very good adviser – albeit one with strong left-wing views. While the likes of Theobald and Georg might be good advisors at lower levels of the hierarchy on specific issues relating to banking and finance, Malikane’s broad credentials should have made him a better choice for a general adviser to a minister. Given that, fortunately, it looks like his manifesto will have no impact whatsoever – with various politicians suddenly realising that talking-up radical economic transformation is a bad idea if it means emptying the fiscus you had planned on appropriating – the most harm done is to Malikane himself. But he has also damaged the possibility of more open discussions about economic and fiscal policy, which means that in fact those who should be most angry with him are economists (including myself) who believe such a conversation is sorely needed.

The bigger picture that Theobald and Georg’s misplaced attacks draw attention to is the state of South African academic economics. Some time ago as a student I witnessed the destructive consequences of the failure by some, otherwise very respectable, academics to reconcile tensions within the local discipline. The result, I think, has been for many to bury their heads in the sand and hope for the best. Or, less innocently, to set-up fiefdoms in which they can propagate their own views and agendas without the inconvenience of differing views.

To be fair to economists, similar behaviour happens in a range of other South African academic disciplines. However, besides the fact that this is an unhealthy state of affairs, legitimate calls for transformation and decolonisation (appropriately defined) will only ratchet-up these tensions and it would be best to address them openly and as maturely as we can. The position I have come to is in some ways rather obvious: we need to raise standards, but we also need a wide diversity of views and therefore should be pluralist in our approach to defining who is a competent economist (academic or otherwise). In that context, we would be advised to avoid doing things like accusing a fellow academic of not being a ‘proper economist’ or being ‘intellectually dishonest’, when they have a PhD from a very reputable North American institution, some competent publications, and extensive engagement and knowledge of South African civil society. When the institutional winds change, you may find that the knives are in your own back. These are surely not the kind of dynamics we want to encourage.

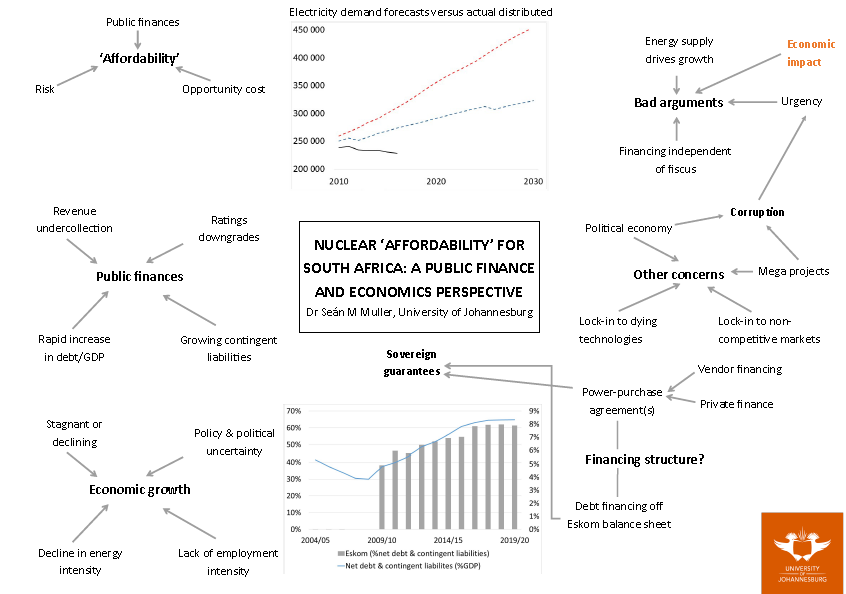

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).