Category: South Africa

Commentary on VAT zero-rating

Since early 2017 I have been engaging with, and advising, some South African civil society organisations on public finance matters. While I naturally have my own views about many issues, the purpose of this engagement is really to help individuals in these organisations understand the issues well enough to make up their own minds. (Some other economists have the more specific agenda of influencing civil society organisations to support their – the economists’ – positions; an approach which I think is evidently dubious).

One important issue that arose with the tabling of the 2018 Budget was the increase in value-added tax (VAT) by one percentage point to 15%. My view on this matter was that there were major procedural and legal problems with how the increase has been brought into effect and that the National Treasury could have done more to protect poor South Africans from the incidence of new revenue measures. The position of civil society has subsequently honed in on the prospect of expanding VAT zero-rating and increasing various forms of social expenditure.

Some of the demands relating to social expenditure that I have seen seem loosely related to the actual VAT incidence claimed by Treasury, but that is a separate issue. More specifically, I recently argued -in an op-ed in Daily Maverick – that zero-rating itself could be of limited value or even counterproductive. A version of that piece with hyperlinks is provided below for anyone interested in reading some of the background references.

Unfortunately, it appears that no-one currently has the appetite to challenge/query the constitutionality of the VAT Act.

Moralising hullaballoo around circulation of The President’s Keepers is misplaced

There was an outcry on South African social media on Saturday the 4th of November, when a PDF version of investigative journalist Jacques Pauw’s book The President’s Keepers began being circulated online and via the WhatsApp messaging service. A number of prominent media, academic and other South African personalities took to social media to criticise the sharing of this file as ‘theft’, ‘stealing’, ‘immoral’ and ‘pirating’. At best, none of those assertions reflect the nuanced complexities around copyright and the public good. At worst, they merely illustrate misinformed armchair moralising.

There appear to be three different, but often overlapping, premises for these arguments. First, that copyright infringement is illegal. Second, that circulating the book as an electronic file will reduce sales and harm profits for the author and publisher. Finally, that there is something inherently morally wrong in circulating a book in a way that allows people who haven’t paid to read it. I want to argue that only the first argument may be correct and that, even then, it doesn’t follow that it is immoral to distribute the book this way.

Illegality

Whether distributing a PDF version of a book you have purchased or received, without any expectation of private gain, is illegal is a question for copyright experts. The illegality could arise in relation to the converting of the original ebook into an electronic form that could be distributed, and the actual distribution itself. To my knowledge, no-one has been attempting to profit from distributing the PDF file and that has legal as well as moral significance.

Even if such distribution is illegal under copyright law, that does not make it inherently immoral: laws inform moral reasoning, are also informed by it, but need not coincide with it. Pauw’s book provides a great example. It is clear that someone would probably have had to break a law in order to give Pauw some of the information he uses, but from a moral standpoint that can be justified by an appeal to the broader public interest. If, for example, the president was letting cigarette distributors make cabinet appointments in return for cash – arguably a treasonous offence – then breaking tax or intelligence laws to reveal this is surely the morally right thing to do. (As a result, in some instances such actions are protected by other laws, in the form of whistleblowing legislation).

A more complex perspective from economics

The more interesting issues relate to the overall impact on the public good of distributing the electronic version of the book. The moralising critiques expressed above appear to be entirely unaware of a large literature, in economics and other disciplines, on the ‘social welfare’ effects of copyright, and copyright infringement.

In economics the fundamental starting point of the literature is that constraints on the distribution of knowledge and information – defined to include everything from the computer code for spreadsheet software to fiction novels – are bad. The reason is simple: in the modern world it is almost costless to reproduce and transmit information, so if that information yields meaningful benefit to a significant number of people then it is socially inefficient for them not to be able to access it. The critical counterweight to this, is that in order to encourage people and institutions to produce such information they need to be able to collect a reasonable return: if people know that information is freely distributed after it has been produced, the producers may realise they will not get a reasonable return and therefore not produce it in the first place.

In recent times, a third dimension has been added to the literature: the role of behavioural and institutional norms. Specifically, the second dimension above is based on a narrow notion of market interaction in which people only pay for something if they are forced to. But it is well-established across a variety of disciplines that human beings often behave in other ways, reciprocating when they don’t have to. The implications of this for markets can be seen from the rise in online organisations, such as Wikipedia, that create and distribute information freely on the basis of a model under which people voluntarily contribute.

Different groups with different consequences

It should be fairly obvious in applying these three perspectives to the case of Pauw’s book, that simplistic moralising is misplaced. If we want to think through the issue systematically, it is useful to distinguish four groups:

- People who already have bought the book

- People who were going to buy the book (i.e. they want to and can afford to) but have not yet done so

- People who would like to read the book but cannot afford to read it

- People who were not going to read the book, whether or not they could afford it.

Initially we can ignore the fourth group: receiving the file makes no difference to them.

One of the strange things about modern publishing is that having the (more expensive) hard copy of a book often doesn’t entitle you to a searchable electronic version. So some people in the first group might benefit if they would later use an electronic version as well, and it would be hard to argue that this is morally or legally illegitimate.

The main interest, however, is in groups two and three: in a basic economic model, the ‘net effect on social welfare’ of distributing the file will depend on the relative numbers of people in these groups, as well as the behaviour of those in group two on receiving the PDF. The well-being of those in group three increases because they can now read the book, whereas cost had prevented them from doing so. What happens to the well-being of those in group two depends on their behaviour, but it certainly will not decrease. The future profits of the publishers and author, on the other hand, depend only on the number of people in group 2 and their behaviour.

As regards group three, it is useful to be reminded of the role that Jacques Pauw is playing. He is an investigative journalist who has a long track record of reporting matters in the public interest. The people who gave him the information used in his book almost certainly did so to bring it to the attention of the South African public, not to make the author or his publishers rich. In other words, the standard concern in the economics literature applies: we want the producers of knowledge to earn a fair due, but we also want the broader social good to be well-served. Given the nature of Pauw’s book, it is not a stretch to argue that it should be disseminated as widely as possible – those who cannot afford the book, the vast majority of South Africans, should not be excluded from reading it.

My own view is that the vast majority of people who were going to buy the book anyway (group two) are unlikely to change their minds just because they received the PDF. One reason is that many people, such as myself, still prefer to read hard copy versions. Another is the principle of reciprocity I noted above: assuming people won’t pay simply because they do not need to ignores vast literatures in psychology, experimental economics and real-world institutions that survive and thrive on the opposite assumption. Furthermore, the hype associated with the distribution of the file could even cause people in group four (who weren’t going to buy the book) to now either read it or buy it.

Some concluding thoughts

In conclusion, let me make a few final points.

First, since we don’t know how different people will react to receiving the ‘pirated’ version of the book, we simply cannot say whether it will increase or decrease sales and profits for the author and publisher. It seems at least as likely that they will increase as decrease, given the arguments I have made above.

Second, given the threats from both the South African Revenue Services and the State Security Agency, it seems reasonable to infer that the PDF file was circulated primarily in anticipation of a possible withdrawal of the book. A second motive may have been to get as many people reading it as possible, because of the serious implications its revelations have for our democracy. In that context, it is hard to understand assertions about ‘theft’.

Third, it is ironic that moralisers implicitly reject the possibility that people might buy the book anyway, out of a spirit of reciprocity, while appealing to recipients to delete the file and buy the book. Essentially, they are presuming, in rather patronising fashion, that only their moral incantations will get people to behave in this way.

Finally, it is important to remember the role that investigative journalists play as conduits of information in the public interest. It is perverse to argue that the first priority in this kind of case is profit when what makes it worthy of such strident commentary is precisely its relevant to matters of national interest.

Fortunately, the author of the book seems to have a more nuanced appreciation of these issues than those ostensibly defending his interest.

There will surely be more such incidents and hopefully we will be able to have a more informed, and less moralising, public exchanges in future.

Declaration: I received two, unsolicited copies of the PDF file containing the book. I didn’t distribute these further, but have filed a copy away: either in the event that I cannot get a hard copy version, or so that once I have done so I can easily search the electronic copy for reference purposes.

Disingenuous economics

Today a new paper in the World Bank Research Observer by announced that there is “no systematic evidence” to support the view that social transfers discourage work. Under different circumstances I might be pleased by this, since I have long believed that claims about welfare-induced voluntary unemployment are mostly ideology-driven garbage. But I am not happy about this paper.

The reason is that the way in which it is written implies that the ‘welfare-induced laziness’ thesis is something conjured up by policymakers and members of the public from thin air. To quote:

despite these proven gains, policy-makers and even the public at large often express concerns about whether transfer programs discourage work.

The authors position themselves, as economists rigorously assessing evidence, against the puzzlingly misguided ‘policymakers’ and ‘public at large’. From this, one would think that economists do not hold such beliefs and have not contributed to them. But you’d be wrong. In fact, a paper published in the World Bank Economic Review in 2003 by Bertrand, Mullainathan and Miller (BMM) claimed that the South African old age pension led young, black men in pension-receiving households to reduce their labour supply. This had a significant impact in South African policy circles, leading a number of local social scientists to challenge the findings of the paper.

Posel, Fairburn and Lund (2006) argued that BMM didn’t adequately account for migration, which changed the conclusions. When I was a Master’s student at UCT in 2006 I wrote a term paper – using data kindly provided by Posel – arguing, further, that BMM’s result using cross-sectional data couldn’t possibly be robust to household formation dynamics:

The primary aim of this paper is demonstrating that, based on existing evidence, one can make at least as strong a case that the pension influences household formation, as that it affects labour supply.

I referred to the BMM paper as a case of ‘perverse priors’. A different approach to the same point by Ranchod (2006) examined the effect of losing a pensioner and his findings called into question the conclusion about labour supply of young men. Ardington, Case and Hosegood (2009) later used panel data to show that differences between households along with migration could explain the finding, rather than an actual reduction in labour supply. To quote them:

Specifically, we quantify the labor supply responses of prime-aged individuals to changes in the presence of pensioners, using longitudinal data collected in KwaZulu-Natal. Our ability to compare households and individuals before and after pension receipt, and pension loss, allows us to control for a host of unobservable household and individual characteristics that may determine labor market behavior. We find that large cash transfers to elderly South Africans lead to increased employment among prime-aged members of their households, a result that is masked in cross-sectional analysis by differences between pension and non-pension households. Pension receipt also influences where this employment takes place. We find large, significant effects on labor migration upon pension arrival.

So, in the South African case, it was well-regarded, US-based economists publishing in a World Bank journal in 2003 who gave credence to the idea that grant receipt led to idleness. Much effort was expended debunking those claims and preventing them from having harmful effects on progressive social policy. It is, therefore, rather outrageous that in 2017 another set of well-regarded, US-based economists publishing in a World Bank journal can pretend as if this never happened.

In my view, this kind of behaviour is characteristic of the failure of critical self-reflection, and taking of responsibility, in economics as a discipline. And it should serve as a cautionary tale to non-economists and economists alike.

Submission to Parliament on Money Bills Act amendments

The Money Bills Act is the legislation that guides Parliament’s oversight of South Africa’s budget and related legislation. I have written previously on that process. The Act has been up for review for some time, and the finance and appropriations committees have had a number of meetings recently to finalise that process. The result is a draft amendment Bill, which I have attempted to explain in an accessible way.

Further to that article, I submitted written comments and made a presentation based on those this week. The audio, relevant documents and meeting report will appear on the relevant Parliamentary Monitoring Group (PMG) website in due course. Access is restricted though, so here are the slides and written submission.

Unfortunately the very limited time available between the call for comments and the deadline for submission (two weeks) also placed some limits on the depth of the analysis. One issue I neglected to address, which was raised by the opposition in the meeting, is that the current Act emphasises – in clause 15(2) – that the PBO should take its work from committees. That is potentially problematic where committee decisions are ultimately determined by a majority party.

Unfortunately, this point became politicised due to disagreements about whether the current committees had allowed partisan considerations to determine what work requests were sent to the PBO. My view is that regardless of what one thinks about the current situation, it is certainly not hard to envisage a situation in which a hypothetical majority party uses its weight on committees to ensure that potentially inconvenient work is not sent the PBO’s way. That could significantly reduce the usefulness of the Office. The broad point I made in my presentation is that our institutions should be designed to be robust to such scenarios. It is for that reason that I agreed with the suggestion that this clause should be amended, or that the clause allowing work to be taken from individual MPs “subject to capacity” – clause 15(3) – be amended to allow the Director discretion based on importance of the request.

It will be interesting to see the final conclusions reached by MPs in relation to these issues and proposals. Given the calibre of MPs on both the majority party and opposition benches on these committees, I am cautiously optimistic that decisions will be taken in the long-term national interest.

Decolonising the South African economics curriculum

This week I attended the ‘Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SOTL) in the South‘ conference hosted by the University of Johannesburg, where I presented a paper entitled: “What would an (South) African economics curriculum look like?”. (A project I have gestured at previously when commenting on discussions around UCT’s economics curriculum – here, here – and promised to do a follow-up on).

The paper can be found in the published conference proceedings here [pdf]. The short slide presentation can be downloaded from here [pdf].

The conference itself was interesting and included a number of different perspectives, and opinions, on the question of ‘decolonisation’. The conclusion I came to was that there are two main aspects to this issue: institutional change and disciplinary change. And in both cases we need to start talking details, because that’s where the really hard work will start and become apparent. In this context, my paper aims to make a contribution in relation to the discipline of economics.

In the end, my discussion of what should go in the curriculum is very limited. One reason is because of the word limit for contributions, but the main reason is that I found there to be many preliminary issues that required fleshing-out first. Some of the more provocative, and important, assertions I make are that:

- Demographic transformation of faculty is important in its own right, but should not be conflated or confused with substantive transformation of the curriculum

- Changing content by introducing certain topics is important but need not lead to the imagined outcomes, it depends on the framing of those topics (e.g. North American economic history arguing that slavery was not such a bad thing)

- The awkward reality that South African academic economics and its institutions is largely characterised by a weak attempt at imitating a lagged, conservative version of the neoclassical mainstream

- A substantively ‘decolonised’ curriculum would be much more challenging than the standard mainstream curriculum – so concerns about ‘lowering of standards’ are misplaced in that context

- Our biggest challenge is the massive gulf between what an ideal, decolonised curriculum looks like and what we (African economists) actually have the capacity to do.

Feedback on any and all aspects of the paper are very welcome.

I intend to get into much more detail regarding an ‘ideal curriculum’ in a second paper, hopefully with some collaborators.

Edit: here is the stand-alone version of my final paper submitted to the SOTL proceedings.

Phase II of pro-nuclear arguments: notes from Nuclear Power Africa 2017

On the 18th of May I attended Nuclear Power Africa, a full day programme on nuclear energy within the broader African Utility Week. I was a little surprised to be invited as a panelist given what I had written previously (here and here) and because I anticipated that an industry conference would be heavily pro-nuclear. As it turned out, I may have been the only panelist who did not have some kind of, direct or indirect, interest in large-scale nuclear procurement proceeding in South Africa. Unsurprisingly, I was also the only panelist arguing that the current case for nuclear is flawed in various respects.

Summary of my argument

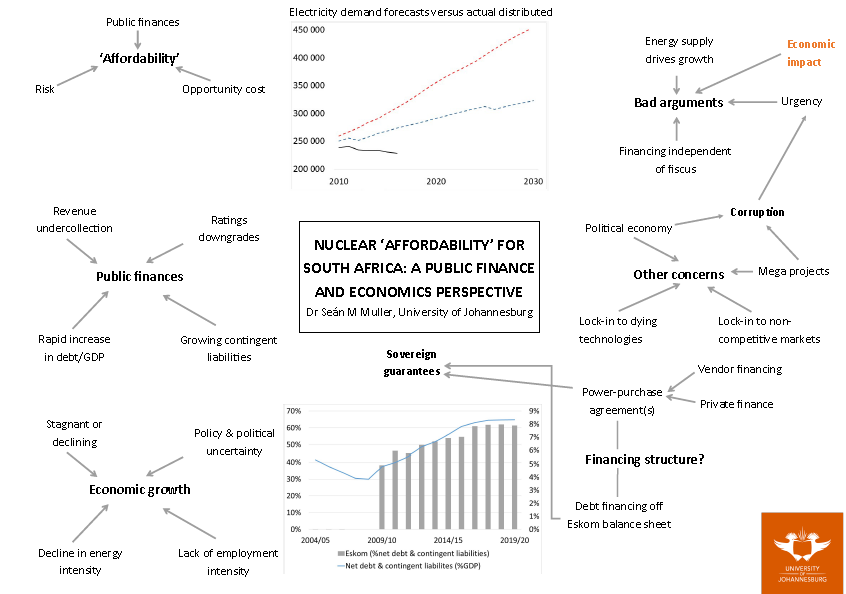

I provided my graphical, one-page summary in a previous post. The basic argument is as captured in my previous articles, but let me briefly repeat it.

South Africa’s public finances are precarious, with stubbornly low economic growth, under-collection of tax revenue alongside additional tax measures, rapid growth in net liabilities (national debt and contingent liabilities such as debt guarantees to Eskom) and of course the recent downgrades – with the possibility of a potentially very damaging downgrade of local currency debt still looming on the horizon.

Meanwhile, electricity demand has not just failed to keep-up with the forecasts from the 2010 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP) on which the need for 9.6GW of nuclear was originally based, it has actually fallen. The following graph is striking:

The red dotted line is the original IRP 2010 baseline forecast, the blue dotted line represents a scenario in the IRP 2010 update (from 2013, but controversially never finalised) entitled ‘Adrift in troubled waters’, and the black line represents actual electricity distributed (based on StatsSA data).

There are, furthermore, various ‘qualitative’ concerns about the programme. Among these:

- Nuclear power projects are particularly prone to many of the ills of ‘mega projects, including cost overruns

- This concern is compounded by the fact that in the South African case the urgency behind the project appears to be due to rent-seeking behaviour (corruption) at the highest political levels

- There is a danger of being locked-in to non-competitive markets (e.g. for nuclear fuel) and increasingly outdated technologies.

There is no chance that a nuclear programme will be financed without government guarantees, whether direct, through Eskom or through power-purchase agreements. This means that ultimately government will carry the associated risks. Combine that fact with the above context and I suggest the conclusion is obvious: there is no case for investing in nuclear now. At best, we could revisit the question in 3 – 5 years’ time depending on trends in economic growth and electricity demand.

Notable pro-nuclear arguments and associated debates

Given the above, it was interesting to hear what proponents of nuclear were using to bolster their position.

The arguments for the urgency of nuclear procurement keep evolving, which is a bad sign: it suggests that a decision has already been taken (for other reasons) and attempts are being made to manufacture substantive arguments after the fact. So even while we engage with these arguments, the issue of motive should not be forgotten.

There are two particularly notable issues that came up at Nuclear Power Africa: the argument that policy models which fail to recommend nuclear are flawed; and, the claim that nuclear procurement will be good for the economy and an important part of industrial policy. Despite somewhat more sophistication on some dimensions, I want to suggest that these new arguments are unconvincing, the case for nuclear remains weak and therefore motivations for advocating it appear dubious.

Are planning models for electricity generation capacity wrong?

One of the most damning arguments against the plan to procure 9.6GW of nuclear energy for South Africa is that the models used to plan energy supply no longer recommend nuclear. The notion that 9.6GW of nuclear was needed came from the Department of Energy’s 2010 Integrated Resource Plan (IRP). That was based on the assumption of significant growth in energy demand, which has not happened – as shown by the second graph above. Furthermore, the cost of renewable energy in South Africa – as established by recent rounds of competitive bidding – has fallen significantly since then. When these factors are taken into account, the base model used for the IRP and similar models used by the Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR) and Energy Research Centre (ERC) do not recommend nuclear. It has been argued (by Anton Eberhard who participated in the Eskom ‘War Room’) that artificial constraints had to be placed on the model used for the draft 2016 IRP in order to produce an outcome in which nuclear is recommended.

The response to this at Nuclear Power Africa, from engineers and economists aligned to institutions pushing for nuclear, was to rubbish the models. This is evidently problematic. If you think a model of this kind has important flaws, then the correct approach is to have a debate about the model structure and parameters. Running the model then rubbishing it because the outcome doesn’t suit your pre-existing conclusion is misguided or disingenuous.

Relatedly, it is concerning that there continues to be a remarkable level of disagreement on even fairly basic technical claims. In a separate session on renewable energy, Tobias Bischoff-Niemz of the CSIR argued that their model accounts for issues like the variable availability of renewables; in the nuclear power session, Eskom’s Chief Nuclear Engineer argued the opposite. And while pro-nuclear speakers cited the example of Germany’s expensive electricity as an illustration of what would happen if South Africa increased its reliance on renewables, Bischoff-Niemz had argued that this was due to Germany investing heavily in renewables at a time when they were much more expensive. It should not be hard to objectively assess these claims.

Economic growth, economic impact and industrial policy

On the economic front, two economists who were in favour of nuclear argued that energy investment must be based on the energy demand associated with the desired level of economic growth. By contrast, I argue that building energy capacity on the basis of wishful thinking could have severe negative consequences for public finances. Rates of growth in economic activity and energy demand are far below what was used to inform the 2010 IRP. It is very unlikely that economic growth will reach the 6% annual growth aimed for in the National Development Plan (NDP) any time soon, if at all. Even the 4% Eskom assumed in its last major tariff application seems improbably optimistic. At best, if economic growth is supposed to be the basis for nuclear procurement, then we should wait a few years in order to get a better sense of the trajectory of growth and how new technologies are affecting the link between growth and the need for electricity from the national grid.

A second set of arguments was put forward by an economist for the Coega Industrial Development Zone, near to where the first nuclear plant might be located. She argued that nuclear procurement would have a significant positive impact on the economy and that even if there was over-investment in energy generation capacity this would be good for industrial development because of low electricity prices.

The economic impact argument is entirely unconvincing. If government indirectly borrows a trillion Rand, either from current or future generations, to invest in anything now that will have an initially large, positive impact on the economy. To paraphrase the famous economist John Maynard Keynes: even if the government just buried that money in the ground and let people dig it up, that would have a large positive impact. The more important question, then, is whether the expenditure is worthwhile: will it provide better social and economic value than alternative investments, and will the debt that future generations have to pay be worth it? At present the answer to both these questions for nuclear is ‘no’. And that also means that this proposal would be bad for the stability and sustainability of public finances.

The argument relating to industrial development is similarly problematic. The positive view that once existed of the extremely low electricity prices South Africa had in the 1990s has been revised. Those low prices were the result of poor management of infrastructure investment: overinvestment in earlier periods followed by a failure of tariffs to include the costs of future investment requirements. But worse still, there is little evidence that the resultant low cost of electricity had any sustainably positive effect on industrial development. The energy-intensive industries that benefitted most are not the most employment-intensive, and have become less so since then. Diverting scarce resources to such industries through an inefficient energy subsidy is a poor argument for nuclear and a bad strategy for Eskom as a state-owned enterprise.

Overall, then, while the arguments for nuclear may be becoming marginally more diverse and sophisticated, but they remain profoundly unconvincing.

The issue of energy generation and industrial policy is, however, a very interesting one on its own regardless of the nuclear debate. Somewhat serendipitously, the Trade and Industrial Policy Strategies (TIPS) Annual Forum happening this week, on the 13th and 14th of June, is on the related topic of “Industrialisation and sustainable growth“.

(unrequited) SARS data request

Earlier this year I wrote about undercollection by the South African Revenue Service (SARS) and the controversy over SARS refunds. This was also discussed during the presentation to Parliament mentioned here. The issue has been bubbling-along for some time – as indicated by this report from SAICA.

The information in the public domain, whether from SARS tax statistics, the SAICA report, or replies to Parliamentary questions, is only suggestive and inadequate for a thorough assessment of whether these concerns have substance or not.

As a result, I decided to follow-up with SARS and request information at the minimum level of detail I believe is required to enable this kind of analysis. I emailed Mr Randall Carolissen – Group Executive, Revenue Analysis, Planning and Reporting and, incidentally, also the Chair of Council at the University of the Witwatersrand – with the request on the 3rd of April. (See the proposed data table here: SARS_statistics_request_table).

Having received no reply, I followed-up on the 22nd of May. To date I have still received no reply. The information requested is at a sufficient level of aggregation that I can’t see any legitimate reason for not making it available. And one might have expected that SARS would be keen for independent researchers to verify their assertions that there has been nothing untoward taking place with refunds.

Recent commentary and analysis: nuclear, Eskom and Molefe

I’ve recently provided commentary and analysis on the somewhat related issues of Brian Molefe’s reappointment as CEO of (South Africa’s national power utility) Eskom, as well as the case against procurement of nuclear energy. An argument that has emerged from Molefe’s backers is that he ‘turned-around’ Eskom during his tenure, while allegations against him remain unproven. Leaving aside the latter claim, in a recent op-ed I argue the credit given to Molefe for the end of load shedding and improvements in certain financial ratios is misplaced. A number of analysts had noted the role of falling demand in ending load shedding, but less attention has been given to the scale and significance of the financial support Eskom received from national government in 2015.

While my preference is to focus on the public finance and public economics dimensions, in the current context one cannot ignore political economy issues. I note here that Molefe’s reappointment is not just concerning for given his alleged improprieties, but more so because of what it implies about the failure of a much wider range of accountability mechanisms that should be keeping dysfunction at Eskom in check.

The failure of those mechanisms has been linked to various vested interests and the push to procure a fleet of nuclear power stations. I’ve previously written on why the current case for nuclear procurement is weak, as are previous, vague claims from Eskom that it can finance the project itself. So I was glad to be invited to debate some of these issues at the recent Nuclear Power Africa stream at Africa Utility Week. (Unfortunately, at the last minute Molefe and Minister Lynne Brown cancelled their scheduled attendance at the conference). As far as I could tell, I was the only panel member who argued that the case for nuclear was weak; given that I was also one of the few who did not have a direct vested interest in nuclear procurement proceeding, this is perhaps not surprising. The range of vested interests – some explicit, others concealed – keeps growing, and that presents its own challenges.

This is the one-page summary I used for my presentation:

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).

(There’s some fun to be had adding more arrows, linking the various issues).

What was clear from the sessions across the day is that, as captured by one report, after a number of setbacks the various nuclear interests (politicians, bureaucrats, academics, utilities and consultants) are ‘regrouping’. The dominant tenor of the talks was that ‘we need to get the broader public to understand why nuclear is good for them’, and that critics – whether energy experts or economists – are simply misguided.

Suffice to say that while the various arguments for immediate nuclear procurement continue to shift and evolve, having listened carefully to them my own view is that they remain unconvincing. I’ll summarise some of the more important areas of contention in my next post, along with some interesting new arguments and why they are flawed.

Statement regarding the Parliamentary Budget Office and recent CCMA award

The Parliamentary Budget Office (PBO) was established to provide Parliament with independent technical advice to support it in exercising oversight of public finances. The importance of this role should be evident given the recent Cabinet reshuffle and ratings agency downgrades, which have raised concerns about public debt, public service pension funds, a prospective nuclear deal and the finances of state-owned enterprises amongst others. These are all matters about which a functioning PBO would be expected to provide credible insight and guidance to Parliamentarians.

There are, however, serious concerns regarding the functioning of the Office. These relate to the content and objectivity of its advice. This became apparent to me shortly after I joined the PBO in 2014. The resulting dynamics in the office led me to resign in 2016, and were also the basis for an unfair labour practice complaint brought against the PBO at the CCMA.

On the 26th of April 2017 the CCMA issued the commissioner’s award, which did not find in my favour on the narrow labour issues raised. While I am disappointed with this outcome, it is important to place the case in the broader context of the need for a competent, functional and credible PBO that is beyond reproach. In this regard, the Commissioner held that – as I had testified – the Director of the PBO had indeed offered to provide me with the interview questions for the position, I had declined the offer, and he had lied about this in his testimony (i.e. under oath). This example was only one of a number of issues raised in the process, but on its own raises very serious questions about the functioning and management of the office.

The Act governing the PBO is expected to be reviewed and amended later this year. In that process, the end goal must remain paramount: to build an independent, technically and ethically credible institution that the public and Members of Parliament can rely on for non-partisan analysis of public finance issues that is conducted without fear or favour.

Internationally, similar institutions are expected to maintain the highest standards of objectivity and political neutrality; standards that the South African PBO has failed to demonstrate. Perhaps the most famous international example is the Canadian PBO, which in 2011 produced a costing for parliamentarians of the government’s fighter jet procurement plan that was significantly higher than the estimates the government had published. The Office was attacked by the Prime Minister at the time, but supported by society at large and subsequently vindicated: government eventually acknowledged that the costs were higher than originally stated and the procurement remains on hold. The Canadian example is in marked contrast to the South African PBO’s analysis of the desirability and feasibility of the proposed nuclear energy procurement. The PBO’s report failed to cost the project, or assess its implications for public finances. In a more recent example from Kenya, the country’s PBO raised concerns about omission of a large increase in debt repayments from budget documents.

Since some of the issues raised at the CCMA go to the heart of these expectations, and it is my view that the basis for its finding is deeply and materially flawed, I am considering taking the award on review to the Labour Court. This is an expensive option – the estimated cost is R500,000 or more, and is prohibitive for an individual. However, the basis on which staff are appointed to, and promoted in, PBOs is one of the most critical factors in their success. Combined with the importance of the PBO and the upcoming amendment of its governing legislation, public interest organisations may find this case to be an appropriate mechanism through which to contribute to the establishment of the kind of PBO the country deserves.